Having enjoyed watching the recent Sky Atlantic television series, Britannia, I decided to find out more about the history behind it. Although it could be said that the series came to the small screen marching on the cloak-tail of the success of Games of Thrones, I found that unlike its illustrious predecessor it is more firmly rooted in history.

School history books may tell us that Julius Caesar ‘Came, saw and conquered’ Britain in 54-55 BC, but the real Roman invasion did not happen for a further ninety years. It took place in 43 AD to be precise, when a force of four legions and auxiliary support (over 30,000 men), sent by Emperor Claudius and under General Aulus Plautius, landed on Britain’s south coast. This was the start of the Roman occupation of Britain – the creation of the Province of Britannia – that would last for three-hundred-and-seventy years. Surely the telling of the story of this pivotal event in British history (albeit in a fictionalised form) is long overdue? Well, here it is – and the series overcomes an unsatisfactory start to reward the viewer with a neatly-constructed and engaging drama.

At the time of the invasion, Britain was an island which was politically fragmented, with multiple tribes each led by a chief, king or queen who – if we believe Roman writers – were constantly at war with one another. Some of the names of the British tribes, such as the Cantii (of Kent), the Trinovantes (of Essex) and the Durotriges (of Dorset), were preserved by the Roman government when they built brand new towns to win the hearts and minds of the indigenous population. Unfortunately, we know very little about the customs, lifestyle, outlook, language or religion of these individual tribes. Some had leaders who actively traded with the Mediterranean world, exchanging locally-produced cattle, grain, metal and slaves for wine, olive oil and exotic forms of glassware and pottery. Others seem to have actively opposed any kind of Roman influence.

At the time of the invasion, Britain was an island which was politically fragmented, with multiple tribes each led by a chief, king or queen who – if we believe Roman writers – were constantly at war with one another. Some of the names of the British tribes, such as the Cantii (of Kent), the Trinovantes (of Essex) and the Durotriges (of Dorset), were preserved by the Roman government when they built brand new towns to win the hearts and minds of the indigenous population. Unfortunately, we know very little about the customs, lifestyle, outlook, language or religion of these individual tribes. Some had leaders who actively traded with the Mediterranean world, exchanging locally-produced cattle, grain, metal and slaves for wine, olive oil and exotic forms of glassware and pottery. Others seem to have actively opposed any kind of Roman influence.

The Roman Empire, which in the early 1st century AD stretched from Spain to Syria, was a resource-hungry superstate and Britain, on its north-western frontier, was a hugely attractive target. This was a land rich in metals (especially iron, tin, lead and gold), cattle and grain. Unfortunately for Rome, Britain lay beyond the civilised world, on the other side of ‘the Ocean’. Just getting there seemed a risky endeavour – especially if, as many Romans believed, the place was full of monsters and barbarians.

Julius Caesar had led two expeditions to southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC and, although these ultimately came to nothing, he had been celebrated in Rome as a hero simply for daring to cross the sea. Caesar’s heirs meddled constantly in British politics, trying to bring order to the frontier-land by helping to resolve disputed royal successions and organising lucrative trade deals. By the time Claudius came to power in AD 41, several British aristocrats had formed alliances with Rome, visiting the city in person to pay their respects and leave offerings to the Roman gods. When the political situation in southern Britain became unstable, with warring tribes threatening both trade and the wider peace, Claudius deployed boots on the ground. The fact that he needed to draw public attention away from difficult issues at home, whilst simultaneously hoping to outdo the military achievements of the great Julius Caesar, probably helped to spur this on.

Julius Caesar had led two expeditions to southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC and, although these ultimately came to nothing, he had been celebrated in Rome as a hero simply for daring to cross the sea. Caesar’s heirs meddled constantly in British politics, trying to bring order to the frontier-land by helping to resolve disputed royal successions and organising lucrative trade deals. By the time Claudius came to power in AD 41, several British aristocrats had formed alliances with Rome, visiting the city in person to pay their respects and leave offerings to the Roman gods. When the political situation in southern Britain became unstable, with warring tribes threatening both trade and the wider peace, Claudius deployed boots on the ground. The fact that he needed to draw public attention away from difficult issues at home, whilst simultaneously hoping to outdo the military achievements of the great Julius Caesar, probably helped to spur this on.

Very little is known about the actual invasion, as no contemporary record survives. The popular view today is that four legions together with auxiliary support, totalling between 30-40,000 soldiers, landed on the Kent coast and fought their way inland. But there is no real archaeological or historical evidence to support this, and the landing point remains the subject of speculation.

What we do know is that the ‘invasion’ appears to have been undertaken in two distinct phases. The first, led by senator Aulus Plautius, was probably a peace-keeping mission, which saw Plautius operating with a small force in order to negotiate a truce between the various British factions whilst hoping to restore certain British refugee monarchs to power. Not all the tribes were opposed to Rome in AD 43 and many leaders would have seen the emperor and his advisors as friends. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, negotiations broke down leaving the emperor no choice to trigger a second phase of the invasion, some months later. This was a calculated display of force, designed to shock and awe enemy elements into submission. Claudius himself led the reinforcements, bringing with him a number of war elephants (he intended to arrive in style). Shortly after, Roman troops marched into Camulodunum (Colchester), the centre of native resistance, and took the formal surrender of 11 British leaders.

Some tribes, like the Trinovantes – based around what is now Colchester – seem to have actively resisted the advance of the Roman legions whilst others, such as the Atrebates (of Berkshire), supported the newcomers and were subsequently very well rewarded. The native town of Camulodunum (Colchester) was subjugated by the Roman military and had a legionary fortress built directly over it. Elsewhere, the Trinovantes were treated as a conquered people whilst the Catuvellauni tribe, who had helped the Romans, were awarded special status in the province and had a brand-new town, full of civic amenities, built for them at Verulamium (St Albans). Having lost the first stage of the war, the British resistance leader Caratacus fled west, stirring up tribes in what is now Wales against Rome. Eventually Caratacus was betrayed by the pro-Roman queen Cartimandua, and handed over to the emperor Claudius in chains.

Some tribes, like the Trinovantes – based around what is now Colchester – seem to have actively resisted the advance of the Roman legions whilst others, such as the Atrebates (of Berkshire), supported the newcomers and were subsequently very well rewarded. The native town of Camulodunum (Colchester) was subjugated by the Roman military and had a legionary fortress built directly over it. Elsewhere, the Trinovantes were treated as a conquered people whilst the Catuvellauni tribe, who had helped the Romans, were awarded special status in the province and had a brand-new town, full of civic amenities, built for them at Verulamium (St Albans). Having lost the first stage of the war, the British resistance leader Caratacus fled west, stirring up tribes in what is now Wales against Rome. Eventually Caratacus was betrayed by the pro-Roman queen Cartimandua, and handed over to the emperor Claudius in chains.

Aulus Plautius was probably nothing like the battle-hardened veteran depicted in the TV series (by tough-talking Mancunian, David Morrissey), being more of a capable and reliable member of Rome’s ruling senatorial class. Although Plautius would have had some experience in the army, he was ultimately a career politician (a safe pair hands) and, for military advice, would have relied on the more experienced legionary officers under his command.

Unlike the male-dominated world of Rome, ancient British society was more egalitarian with both men and women wielding political and military power. We know very little about the command structure of British tribal armies opposing Rome during the invasion. Although the names of some leaders survive on Celtic coins and in the pages of Roman writers and historians, there is, unfortunately, no historical evidence (yet) for the female war leaders Antedia and Kerra (played by Zoë Wanamaker and Kelly Reilly in the TV series).

Unlike the male-dominated world of Rome, ancient British society was more egalitarian with both men and women wielding political and military power. We know very little about the command structure of British tribal armies opposing Rome during the invasion. Although the names of some leaders survive on Celtic coins and in the pages of Roman writers and historians, there is, unfortunately, no historical evidence (yet) for the female war leaders Antedia and Kerra (played by Zoë Wanamaker and Kelly Reilly in the TV series).

A king called Antedios certainly seems to have ruled in Norfolk just prior to the invasion whilst the leader of the British resistance was a king called Caratacus (who later became target number one for the Roman government). There were certainly strong and militarily capable women within the British tribal armies – this was a point often used by Roman generals in an attempt to ridicule their foe. Later, in the AD 60s, Queens Cartimandua of the Brigantes (in Yorkshire) and Boudicca of the Iceni (in Norfolk) emerge. Both, however, were, at least during the early stages of the invasion, firm supporters of Rome, seeing the obvious benefits of siding with a Mediterranean superpower.

In popular culture, the druids are usually seen as being integral to Celtic society: part mystical, religious teachers and part hard-line resistance leaders, constantly stirring up trouble for Rome. The problem is that we really have very little evidence for their existence in Britain. In Gaul (France), Julius Caesar had noted their presence in the mid-50s BC, but there is only one definite reference to them in the British Isles, on the island of Anglesey where, so the Roman writer Tacitus tells us, they were committing acts of human sacrifice in AD 60. Modern writers and historians tend to view druids as part of an all-encompassing religion (druidism) and, thanks to fictional accounts (most notably in the stories of Asterix the Gaul) suggest that every tribe would have had one: a prehistoric equivalent, perhaps, of a parish priest or holy man. The trouble is, as plausible as this theory may appear, there is absolutely no evidence for this.

In popular culture, the druids are usually seen as being integral to Celtic society: part mystical, religious teachers and part hard-line resistance leaders, constantly stirring up trouble for Rome. The problem is that we really have very little evidence for their existence in Britain. In Gaul (France), Julius Caesar had noted their presence in the mid-50s BC, but there is only one definite reference to them in the British Isles, on the island of Anglesey where, so the Roman writer Tacitus tells us, they were committing acts of human sacrifice in AD 60. Modern writers and historians tend to view druids as part of an all-encompassing religion (druidism) and, thanks to fictional accounts (most notably in the stories of Asterix the Gaul) suggest that every tribe would have had one: a prehistoric equivalent, perhaps, of a parish priest or holy man. The trouble is, as plausible as this theory may appear, there is absolutely no evidence for this.

Article Source: www.historyextra.com

Britannia Publicity photos by Sky UK Ltd.

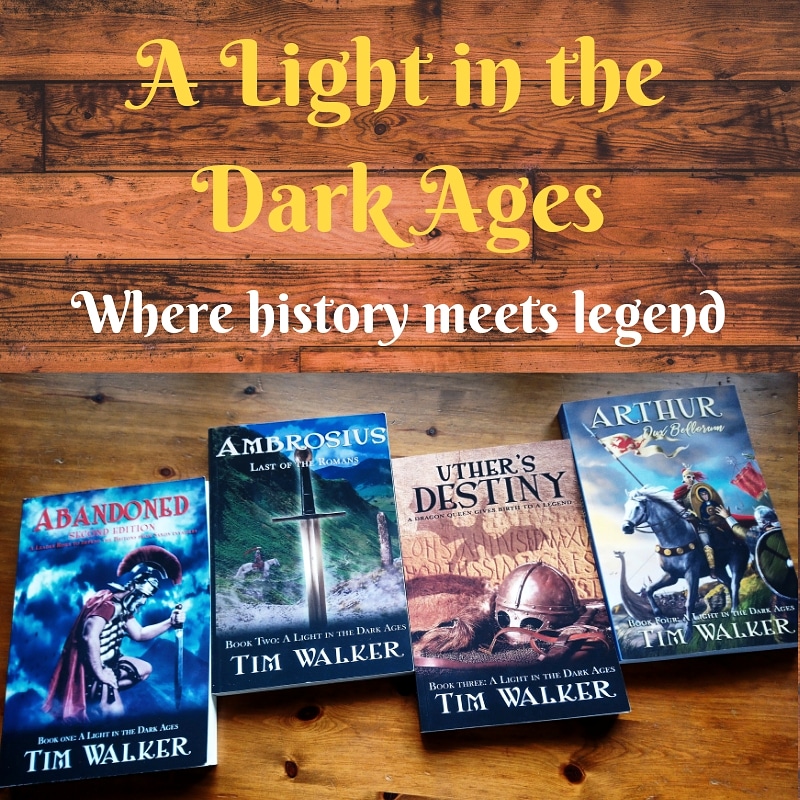

In reading about the origins of the King Arthur story, I became fascinated by the blurred boundary between historical fact and storytelling. The oral tradition of remembering great heroes and their deeds, who often protected a fearful community from an external threat, delivered through bardic praise poems, songs and dramatic performance, often has a root in factual events and real people. But by their nature, the feats of the hero are exaggerated and he is ‘bigged-up’ to make for a more engaging story. The bard, after all, was singing for his supper. The feats of an heroic warrior is a recurring theme in many of our favourite legends including Beowulf – the earliest epic poem in the English language; George and the Dragon and Robin Hood.

In reading about the origins of the King Arthur story, I became fascinated by the blurred boundary between historical fact and storytelling. The oral tradition of remembering great heroes and their deeds, who often protected a fearful community from an external threat, delivered through bardic praise poems, songs and dramatic performance, often has a root in factual events and real people. But by their nature, the feats of the hero are exaggerated and he is ‘bigged-up’ to make for a more engaging story. The bard, after all, was singing for his supper. The feats of an heroic warrior is a recurring theme in many of our favourite legends including Beowulf – the earliest epic poem in the English language; George and the Dragon and Robin Hood.

The narrative thrust is loosely guided by the writings of Geoffrey of Monmouth in his 1136 work, The History of the Kings of Britain. The romantic in me likes to think there might be some credence in his account of events in fifth century Britannia leading up to the coming of King Arthur (now widely thought to be a composite of a number of leaders who organised opposition to the spread of Anglo-Saxon colonists).

The narrative thrust is loosely guided by the writings of Geoffrey of Monmouth in his 1136 work, The History of the Kings of Britain. The romantic in me likes to think there might be some credence in his account of events in fifth century Britannia leading up to the coming of King Arthur (now widely thought to be a composite of a number of leaders who organised opposition to the spread of Anglo-Saxon colonists).

At the time of the invasion, Britain was an island which was politically fragmented, with multiple tribes each led by a chief, king or queen who – if we believe Roman writers – were constantly at war with one another. Some of the names of the British tribes, such as the Cantii (of Kent), the Trinovantes (of Essex) and the Durotriges (of Dorset), were preserved by the Roman government when they built brand new towns to win the hearts and minds of the indigenous population. Unfortunately, we know very little about the customs, lifestyle, outlook, language or religion of these individual tribes. Some had leaders who actively traded with the Mediterranean world, exchanging locally-produced cattle, grain, metal and slaves for wine, olive oil and exotic forms of glassware and pottery. Others seem to have actively opposed any kind of Roman influence.

At the time of the invasion, Britain was an island which was politically fragmented, with multiple tribes each led by a chief, king or queen who – if we believe Roman writers – were constantly at war with one another. Some of the names of the British tribes, such as the Cantii (of Kent), the Trinovantes (of Essex) and the Durotriges (of Dorset), were preserved by the Roman government when they built brand new towns to win the hearts and minds of the indigenous population. Unfortunately, we know very little about the customs, lifestyle, outlook, language or religion of these individual tribes. Some had leaders who actively traded with the Mediterranean world, exchanging locally-produced cattle, grain, metal and slaves for wine, olive oil and exotic forms of glassware and pottery. Others seem to have actively opposed any kind of Roman influence. Julius Caesar had led two expeditions to southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC and, although these ultimately came to nothing, he had been celebrated in Rome as a hero simply for daring to cross the sea. Caesar’s heirs meddled constantly in British politics, trying to bring order to the frontier-land by helping to resolve disputed royal successions and organising lucrative trade deals. By the time Claudius came to power in AD 41, several British aristocrats had formed alliances with Rome, visiting the city in person to pay their respects and leave offerings to the Roman gods. When the political situation in southern Britain became unstable, with warring tribes threatening both trade and the wider peace, Claudius deployed boots on the ground. The fact that he needed to draw public attention away from difficult issues at home, whilst simultaneously hoping to outdo the military achievements of the great Julius Caesar, probably helped to spur this on.

Julius Caesar had led two expeditions to southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC and, although these ultimately came to nothing, he had been celebrated in Rome as a hero simply for daring to cross the sea. Caesar’s heirs meddled constantly in British politics, trying to bring order to the frontier-land by helping to resolve disputed royal successions and organising lucrative trade deals. By the time Claudius came to power in AD 41, several British aristocrats had formed alliances with Rome, visiting the city in person to pay their respects and leave offerings to the Roman gods. When the political situation in southern Britain became unstable, with warring tribes threatening both trade and the wider peace, Claudius deployed boots on the ground. The fact that he needed to draw public attention away from difficult issues at home, whilst simultaneously hoping to outdo the military achievements of the great Julius Caesar, probably helped to spur this on. Some tribes, like the Trinovantes – based around what is now Colchester – seem to have actively resisted the advance of the Roman legions whilst others, such as the Atrebates (of Berkshire), supported the newcomers and were subsequently very well rewarded. The native town of Camulodunum (Colchester) was subjugated by the Roman military and had a legionary fortress built directly over it. Elsewhere, the Trinovantes were treated as a conquered people whilst the Catuvellauni tribe, who had helped the Romans, were awarded special status in the province and had a brand-new town, full of civic amenities, built for them at Verulamium (St Albans). Having lost the first stage of the war, the British resistance leader Caratacus fled west, stirring up tribes in what is now Wales against Rome. Eventually Caratacus was betrayed by the pro-Roman queen Cartimandua, and handed over to the emperor Claudius in chains.

Some tribes, like the Trinovantes – based around what is now Colchester – seem to have actively resisted the advance of the Roman legions whilst others, such as the Atrebates (of Berkshire), supported the newcomers and were subsequently very well rewarded. The native town of Camulodunum (Colchester) was subjugated by the Roman military and had a legionary fortress built directly over it. Elsewhere, the Trinovantes were treated as a conquered people whilst the Catuvellauni tribe, who had helped the Romans, were awarded special status in the province and had a brand-new town, full of civic amenities, built for them at Verulamium (St Albans). Having lost the first stage of the war, the British resistance leader Caratacus fled west, stirring up tribes in what is now Wales against Rome. Eventually Caratacus was betrayed by the pro-Roman queen Cartimandua, and handed over to the emperor Claudius in chains. Unlike the male-dominated world of Rome, ancient British society was more egalitarian with both men and women wielding political and military power. We know very little about the command structure of British tribal armies opposing Rome during the invasion. Although the names of some leaders survive on Celtic coins and in the pages of Roman writers and historians, there is, unfortunately, no historical evidence (yet) for the female war leaders Antedia and Kerra (played by Zoë Wanamaker and Kelly Reilly in the TV series).

Unlike the male-dominated world of Rome, ancient British society was more egalitarian with both men and women wielding political and military power. We know very little about the command structure of British tribal armies opposing Rome during the invasion. Although the names of some leaders survive on Celtic coins and in the pages of Roman writers and historians, there is, unfortunately, no historical evidence (yet) for the female war leaders Antedia and Kerra (played by Zoë Wanamaker and Kelly Reilly in the TV series). In popular culture, the druids are usually seen as being integral to Celtic society: part mystical, religious teachers and part hard-line resistance leaders, constantly stirring up trouble for Rome. The problem is that we really have very little evidence for their existence in Britain. In Gaul (France), Julius Caesar had noted their presence in the mid-50s BC, but there is only one definite reference to them in the British Isles, on the island of Anglesey where, so the Roman writer Tacitus tells us, they were committing acts of human sacrifice in AD 60. Modern writers and historians tend to view druids as part of an all-encompassing religion (druidism) and, thanks to fictional accounts (most notably in the stories of Asterix the Gaul) suggest that every tribe would have had one: a prehistoric equivalent, perhaps, of a parish priest or holy man. The trouble is, as plausible as this theory may appear, there is absolutely no evidence for this.

In popular culture, the druids are usually seen as being integral to Celtic society: part mystical, religious teachers and part hard-line resistance leaders, constantly stirring up trouble for Rome. The problem is that we really have very little evidence for their existence in Britain. In Gaul (France), Julius Caesar had noted their presence in the mid-50s BC, but there is only one definite reference to them in the British Isles, on the island of Anglesey where, so the Roman writer Tacitus tells us, they were committing acts of human sacrifice in AD 60. Modern writers and historians tend to view druids as part of an all-encompassing religion (druidism) and, thanks to fictional accounts (most notably in the stories of Asterix the Gaul) suggest that every tribe would have had one: a prehistoric equivalent, perhaps, of a parish priest or holy man. The trouble is, as plausible as this theory may appear, there is absolutely no evidence for this.

Ambrosius finds that the influence of Rome is fast becoming a distant memory, as Britannia reverts to its Celtic tribal roots. He joins forces with his adoptive brother, Uther Pendragon, and they are guided by their shrewd father, Marcus, as he senses his destiny is to lead the Britons to a more secure future.

Ambrosius finds that the influence of Rome is fast becoming a distant memory, as Britannia reverts to its Celtic tribal roots. He joins forces with his adoptive brother, Uther Pendragon, and they are guided by their shrewd father, Marcus, as he senses his destiny is to lead the Britons to a more secure future.

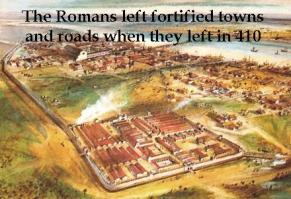

This was also the year that Rome was sacked by the Visigoths under their king, Alaric, as barbarian tribes from the east swept across Europe. Roman authority was briefly restored after paying off the barbarians, but they would not go away, and the final collapse came in 476 when the last western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by Odoacer, whose father was purported to have been an adviser to Attila the Hun. The sun had set on a civilised and ordered way of life, to be replaced with tribal warfare, economic ruin and insecurity for the peoples of Europe.

This was also the year that Rome was sacked by the Visigoths under their king, Alaric, as barbarian tribes from the east swept across Europe. Roman authority was briefly restored after paying off the barbarians, but they would not go away, and the final collapse came in 476 when the last western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by Odoacer, whose father was purported to have been an adviser to Attila the Hun. The sun had set on a civilised and ordered way of life, to be replaced with tribal warfare, economic ruin and insecurity for the peoples of Europe. To some extent, the period of the Dark Ages remains obscure to modern onlookers. The term employs traditional light-versus-darkness imagery to contrast the ‘darkness’ of the period in question with earlier and later periods of ‘light’. The tumult of the era, its religious and tribal conflicts and debatable time period, all work together to obscure it from our eyes. Scarcity of sound literature and cultural achievements marked these years, and barbaric practices prevailed. The leaders of the time are merely names without faces; nor are there accurate records of their deeds.

To some extent, the period of the Dark Ages remains obscure to modern onlookers. The term employs traditional light-versus-darkness imagery to contrast the ‘darkness’ of the period in question with earlier and later periods of ‘light’. The tumult of the era, its religious and tribal conflicts and debatable time period, all work together to obscure it from our eyes. Scarcity of sound literature and cultural achievements marked these years, and barbaric practices prevailed. The leaders of the time are merely names without faces; nor are there accurate records of their deeds. In our own time, some believe we are entering a new dark age, characterised not by the absence of written records, but by a plethora of false information aimed at confusing and distracting us from real events. The World Wide Web was given to us by its inventor, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, to encourage the free exchange of information. But we have failed to safeguard it, and it has now been hijacked by thieves and those with extreme political agendas whose aim is to enslave us and strip us of our rights and dignity. ‘Fake News’ is a tactic used by unscrupulous politicians to terrify and confuse, leaving us susceptible to exploitation and undermining our democratic systems with lies and false promises.

In our own time, some believe we are entering a new dark age, characterised not by the absence of written records, but by a plethora of false information aimed at confusing and distracting us from real events. The World Wide Web was given to us by its inventor, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, to encourage the free exchange of information. But we have failed to safeguard it, and it has now been hijacked by thieves and those with extreme political agendas whose aim is to enslave us and strip us of our rights and dignity. ‘Fake News’ is a tactic used by unscrupulous politicians to terrify and confuse, leaving us susceptible to exploitation and undermining our democratic systems with lies and false promises.

Following useful feedback from a reader’s group, I have made some changes and ironed out a few glitches to my long short story, ABANDONED! A revised version is now available to download from amazon kindle at the derisory price of £0.99 or equivalent in other amazon territories.

Following useful feedback from a reader’s group, I have made some changes and ironed out a few glitches to my long short story, ABANDONED! A revised version is now available to download from amazon kindle at the derisory price of £0.99 or equivalent in other amazon territories.

I started writing this as a short story but it took on a life of its own and grew and grew, finally reaching its end at over 13,000 words. This makes it a literary hybrid – too long for a short story, and too short for a novella. However, it does qualify as a

I started writing this as a short story but it took on a life of its own and grew and grew, finally reaching its end at over 13,000 words. This makes it a literary hybrid – too long for a short story, and too short for a novella. However, it does qualify as a